Broadstreet bulletin – Issue 1

The return of inflation?

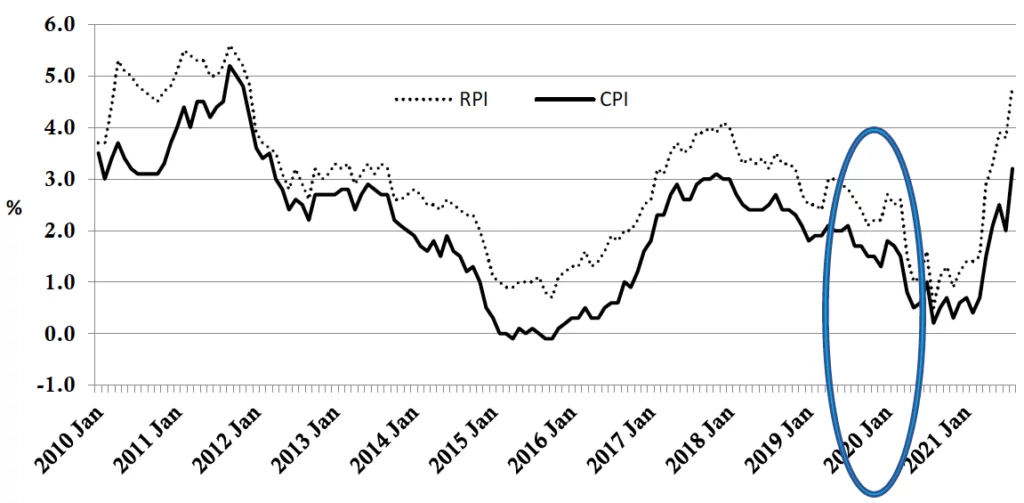

In September 2020, annual inflation in the UK was running at 0.5% on the CPI measure and 1.1% using the old RPI yardstick. At the time price rises were the least of the economic concerns. Wind forward 12 months and inflation has become a hot topic. The latest (August) figures are 3.2% CPI and 4.8% RPI. The increase was the highest monthly CPI rise ever recorded by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and brings the inflation rate to the level last seen in March 2012. As the graph shows, 2021 has seen something of an inflationary renaissance.

RPI and CPI 2010 onwards

Source: ONS

Not only here…

Inflation was once known as the ‘British disease’, reflecting the problems of the 1970s when annual price increases topped 20%. This time around, the UK is not alone in experiencing a jump in prices. Across the Atlantic, the USA has seen inflation leap from 1.4% last September to a 13-year high of 5.4% in June and July 2021, before easing to 5.3% in August.

The Eurozone, which has long struggled to meet its inflation target, has joined in too: prices were falling by 0.3% a year in September 2020, whilst in August 2021 they were rising at 3% – the highest since November 2011 and well above the European Central Bank’s new central target of 2%.

‘Transitory’, say the central bankers…

The favourite word used by central bankers to describe the uptick in inflation is ‘transitory’. There is a case to be made for that view:

- Annual inflation is a measure of current prices against those a year ago. Think back twelve months and there are some prices that were driven down by the pandemic, which cut or even eliminated demand. Look across two years and the price of an item might have changed little, but the movement during the period could be V-shaped, with the last 12 months’ sharp bounce back. ‘Base effects’ is the economists’ term for this statistical quirk. Another year and they could automatically disappear.

- The pandemic has also created supply chain issues which have driven up prices as demand recovered. A good example has been the supply of computer chips used in car production. One vehicle may need up to 1,500 chips and these have been in short supply, with a knock-on effect for car production. In the absence of sufficient new vehicles, second-hand car prices have jumped – by over 18% in the year to August in the UK. Once more, the argument is in another 12 months’ supply chains will have re-established and the problem will have disappeared

…But are they right?

The argument against the central bankers’ optimism is partly that ‘they-would-say-that-wouldn’t-they?’ If they thought that the spike in inflation was more than a blip, then the central bankers would need to reverse their current policies of keeping interest rates around zero and buying large quantities of their Governments’ bonds. Such a change would have serious consequences for the Governments concerned, all of which have borrowed heavily in response to the pandemic and can ill-afford a higher interest bill.

The worry is that price inflation is already starting to work through into wage increases, although there are distortions here too – in July, average pay in the UK was up 8.3% year on year. Wage rises could then lead to further price rises and so the spiral begins…

Why inflation matters

For the last 20 years to the end of 2020, CPI inflation averaged 2.1% and RPI inflation 2.9%. That has been close enough to the Bank of England’s target to be of no concern. An inflation rate of 4-5% would start to have a serious impact on investment and financial planning. At 5%, purchasing power halves over 14 years, whereas at 2% the same erosion takes place across 35 years.

Higher inflation would probably also mean higher interest rates. That could drive down the value of many investments, simply because the higher the interest rate, the lower the discounted value of future investment income.

As far as possible, your financial planning – from basic life cover to portfolio investment – should take account of inflation. Recent decades of low inflation have reduced the cost of ignoring this principle, but it may prove an expensive error going forward – do you want your retirement living standards to halve every 14 years..?

The return of inflation?

The UK tax system is notorious for its complexity. Every year seems to get worse, with a fresh Finance Act adding a few hundred more pages of legislation – this year’s Act ran to 417 pages. One of the more bizarre aspects of our tax system is the tax year 6 April starting date for individuals, rather than a more logical date such as 1 January (chosen by many countries) or even 1 April.

Blame history

That 6 April date has its roots in England’s distant past. It began life as 25 March (Lady Day), which was New Year’s Day in England from the middle of the 12th century. The introduction of the Gregorian calendar in 1752 and an anomalous leap year in 1800 resulted in an extra 12 days being added, to arrive at the current 6 April date. Both additions were driven by Governments anxious to keep 365 days of revenue in one tax year.

The Office of Tax Simplification reviews a revision

In June, the Office of Tax Simplification (OTS) announced that it would be undertaking ‘a high-level exploration and analysis of the benefits, costs and wider implications of a change in the date of the end of the UK tax year for individuals’. Somewhat disappointingly, the OTS said its focus would be on moving the end of the tax year to 31 March, which would align it with the Government’s own financial year and the corporation tax year.

However, the OTS did also promise to ‘outline the main additional broader issues’ of a move to align the tax year with the calendar year. Interestingly, just such a change was undertaken by Ireland in 2002, when it had a shortened tax year running from 6 April 2002 to 31 December 2002.

When the OTS published its review on 15 September, unsurprisingly, it confirmed that a clear majority of those responding thought that the UK should adopt a different year end. Alas, their wish will not be granted, at least in the short term. The OTS recommended that any change should wait until after major HMRC projects have been completed, such as the Single Customer Account and Making Tax Digital (MTD) for income tax.

HMRC has its own ideas

In the month after the OTS’s June review announcement, HMRC weighed in with a consultation paper on another aspect of the tax calendar; the taxation of the self-employed, including partnerships. HMRC’s proposals revolved around that key 6 April date and made no mention of the OTS work.

Currently, the ‘basis year’ approach means that the self-employed generally pay tax on the profits earned in their trading year ending in the tax year. The choice of trading year is down to the individual or partnership. So, for example, if you have a trading year that runs from 1 May to the following 30 April, in the 2021/22 tax year, you will be taxed on the profits earned in your trading year 1 May 2020 to 30 April 2021.

HMRC wants to change the basis year method to mean that the self-employed are taxed on what they earn during a tax year. The consultation paper says this is necessary as part of its MTD for income tax programme and would take effect from 6 April 2023. Such a reform would have two important consequences:

- From 2023/24 onwards, to arrive at profit figures for the tax return, it would be necessary to pro-rata profits from two trading years. Taking that 30 April year end again, in 2023/24, tax would be calculated by apportioning profits in the trading years to 30 April 2023 (25 days’ worth) and to 30 April 2024 (341 days’ worth). Anyone with a trading period ending late in the tax year, e.g. 31 December, could be forced to give an estimate if their accounts are not ready by the 31 January return filing date. An adjustment would then need to be made once accurate figures became available.

- 2022/23 – next tax year – would be a transitional year in which all profits to 5 April 2023 not previously taxed would be taken into account. The result could be nearly two years’ profits taxable in a single tax year. For that 30 April year end, in 2022/23 the taxable profits would be from 1 May 2021 to 5 April 2023 – over 23 months’ worth – again calculated on an apportionment basis across two sets of accounts. HMRC acknowledges the impact this would have on personal tax bills and suggests ‘excess profits’ could be spread over five tax years.

The HMRC proposals have received predictably wide criticism, with many tax professionals saying they are being forced through far too quickly – even the consultation period was halved to six weeks, most of which fell in August. Others have suggested the idea was just another example of the Treasury’s familiar money-raising ruse of accelerating tax payments.

If you have the sense that any real reduction in the complexity of the UK tax system is as distant as ever, you are probably correct. With Government borrowing at record levels, any ‘simplification’ that does eventually emerge from the current proposals is likely to hide higher and/or faster tax payments. Guidance on tax planning will continue to be vital.

Pensions lifetime allowance

One of the subtle tax increases introduced in the March 2021 Budget was a freezing of the pensions lifetime allowance until April 2026 at its 2020/21 level of £1.0731m. Like any freezing of an allowance, it is designed to produce extra tax as inflation and/or economic growth drag more taxpayers over the fixed threshold.

What is the relevance of the lifetime allowance?

The lifetime allowance sets a ceiling on the value of pension benefits, above which:

- A 25% tax charge applies if benefits are drawn as income; or

- A 55% tax charge applies on lump sum benefits.

The standard lifetime allowance was introduced in 2006 at a level of £1.5m and gradually increased to £1.8m four years later. Thereafter the value has either been frozen, cut, or, more recently, increased in line with inflation (prices, not the more logical earnings).

The Treasury’s interventions since 2010 have been designed to constrain pension savings and thereby reduce the tax relief it has to grant on contributions. It is a moot point whether the lifetime allowance itself was meant to produce tax via those two tax charges. Like much anti-avoidance legislation, the intention behind the lifetime allowance tax charge was to discourage action that could trigger a tax bill.

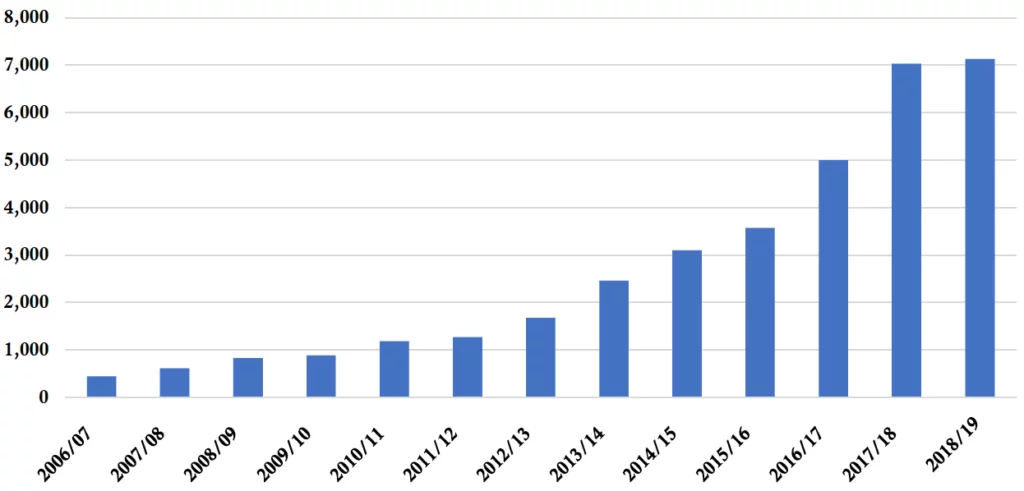

Growing more relevant

As the graph above illustrates, the number of people being caught by the lifetime allowance has increased sharply in recent years. The latest data, for 2018/19, shows an average tax charge of nearly £40,000. The lifetime allowance freeze is set to increase both those falling foul of the lifetime allowance tax charge and the average amount they pay.

In some instances, the lifetime allowance is unavoidable or worth accepting. For example:

- If your employer will not offer a financial alternative to pension contributions, the choice is between a benefit net of the lifetime allowance charge (maximum 55% tax) or no benefit (effectively 100% tax).

- You may have a pension pot well under the lifetime allowance shortly before drawing benefits and then find a sudden spurt of investment growth pushes the pot’s value over the allowance. For example, a fund worth £900,000 on 25 August 2020 would have grown to £1,135,890 a year later, if it had moved in line with the FTSE All-Share Index.

- In some cases, the lifetime allowance charge may be worth accepting as it is less than the combined value of income tax and employer national insurance (NIC) relief on an employer pension contribution.

There have been rumours that the next Budget will see the lifetime allowance cut again, perhaps to as little as £800,000.

7 September non-Budget

Major tax and social care changes

In early September a triumvirate of the Prime Minister, Chancellor and Health Secretary presented the Government’s long-awaited plans for the reform of social care in England (the devolved nations each have their own framework). The statement from the Chancellor alone contained large enough tax changes to have constituted a Budget in quieter times.

Funding of social care: the non-tax costs

The proposed changes would mean that if you enter residential care in England from October 2023 onwards:

- If you have assets above £100,000, you will still have to pay full care costs. If you are single, your main home will be included as an asset, but if you have a partner or dependent living in the property, its value will normally be ignored. The current capital ceiling is just £23,250 and this will continue to apply for anyone entering care before October 2023.

- There will be a new lifetime cap of £86,000 on the amount that you will need to spend on personal care costs. The costs of your accommodation and food – so-called hotel costs – will fall outside the new cap.

- If you have assets below £20,000 (current ceiling £14,250), you will not be required to use your savings (or the value of your home) for care costs, but you may need to make a contribution from your income.

- If you have assets in the £20,000-£100,000 range, you will be expected to make a contribution from your income. In this instance income includes ‘tariff income’, which is notional income from capital above £20,000. The proposals say this will be ‘no more than 20%’ (currently 20.8%). For example, if you had capital of £80,000 your ‘tariff income’ would be deemed to be £12,000 a year, all of which could go towards meeting your care costs.

Funding of social care: the tax costs

To finance the higher capital means-testing limits and the £86,000 cap, the Government announced the introduction of increased NICs under the guise of a new Health and Social Care Levy (HSCL):

- In the next tax year (2022/23) the HSCL will be applied as a 1.25% increase in Class 1 (both employer and employee) and Class 4 main and higher rates of NICs.

- From 2023/24, NIC rates will return to their 2021/22 level and the HSCL will become a separate 1.25% charge applied to all employed and self-employed earnings. However, unlike NICs, from 2023/24 the HICL will be paid on the earnings of employees and the self-employed above state pension age (SPA – currently 66). At present only employers pay NICs on employees beyond SPA.

NICs – before and after

| Tax year | Employee Main/Higher | Employer | Self-employed Main/Higher |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021/22: NICs | 12%/2% | 13.8% | 9%/2% |

| 2022/23: NICs | 13.25%/3.25% | 15.05% | 10.25%/3.25% |

|

2023/24: NICs HSCL |

12%/2% 1.25% |

13.8% 1.25% |

9%/2% 1.25% |

|

Threshold (2021/22) Main: Higher: |

£9,568 £50,270 |

£8,840 N/A |

£9,568 £50,270 |

From April 2022, tax on dividends will also increase by 1.25%, as shown in the table below:

Dividend tax – before and after

| Tax year | Basic rate | Higher rate | Additional rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021/22 | 7.5% | 32.5% | 38.1% |

| 2022/23 onwards | 8.75% | 33.75% | 39.35% |

Funding of social care: the state pension cost

While the focus was on the social care announcement, the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) revealed that it would suspend the operation of the State Pension Triple Lock for the coming year only. Instead, there will be a Double Lock, meaning the basic and new State Pension will increase by the greater of:

- 2.5%; and

- CPI inflation to September 2021

The DWP estimated that the switch to a Double Lock will ‘…mean a difference of around £4 or 5 billion in basic and new State Pensions expenditure in 2022/23’, which compares with the £12bn generated by the NIC and dividend tax changes. The Double Lock saving is not a one-off but an annual reduction in expenditure, as all future State Pension increases will be from a lower base than would otherwise have been the case.

The increases to NICs and dividends represent a major reform to the tax system and will have important consequences, particularly if you are a company owner-director or self-employed. In practice, the changes to social care funding – two years away, do not forget – could still leave you facing potentially large costs to meet. The Government’s own example suggests it is only those who stay in a care home over three years and four months who stand to benefit from the cap.

27 October real Budget

The Budget cycle has been thoroughly disrupted over the past five years. It all started when Phillip Hammond (two Chancellors ago) announced in November 2016 that he would be reverting to an Autumn Budget from the following year, but would nevertheless have a Spring 2017 Budget. After two Budgets in 2017, there was one Autumn Budget in 2018, but then 2019 had no Budgets because of the impending election. 2020 started with a Spring Budget to make up for the loss of 2019, but then morphed into a series of pandemic-related quasi-Budget announcements by the Chancellor. Covid-19 also forced the Chancellor to abandon an Autumn 2020 Budget in favour of a Spring 2021 Budget, when it was hoped the economic outlook would be clearer.

Where are we now?

A week after the House of Commons had risen for its summer recess in July, the Chancellor announced that he had asked the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) to prepare an economic and fiscal outlook (EFO) to be presented on 27 October. Normally EFOs appear alongside Budgets or formal statements, but, at that time, Mr Sunak made no mention of either.

However, alongside the raft of social care announcements on 7 September, the Chancellor confirmed 27 October as the Autumn Budget date.

Plenty to watch out for

Despite the £12bn of tax raising revealed on 7 September, the Chancellor still has a challenging to do list:

- Government debt In 2020/21, the Government borrowed about £300bn, over five times the figure for the previous year. In the first five months of this financial year another £93.8bn has been added to the debt pile. The occupant of 11 Downing Street will not want to see any of his neighbour’s spending plans unmatched by tax increases.

- Inheritance tax In response to a request from Philip Hammond, the OTS produced two reports on simplifying inheritance tax (IHT), the last of which emerged just over two years ago. To date the Chancellor has done little more in response than freeze the nil rate band until 2026 and promise to reduce IHT paperwork for most estates.

- Capital gains tax IHT is not the only capital tax that has two OTS reports sitting on Mr Sunak’s desk. The same is true of capital gains tax (CGT) – and these were reports which he had personally commissioned. CGT is not a tax for which there was a manifesto promise of no rate changes, so the Treasury views it as a promising area for raising more revenue. For example, the OTS suggested reducing the annual exemption from £12,300 to £2,000- £4,000 and aligning CGT rates (maximum generally 20%) with income tax rates (maximum 45% in England).

The Chancellor has no money for giveaways, and, even before the increases to NICs and dividend tax, he was already quietly increasing taxes by freezing allowances and tax bands.

No comment yet, add your voice below!